“To those who would see the Maine wilderness, tramp day by day through a succession of ever delightful forest, past lake and stream, and over mountains, we would say: Follow the Appalachian Trail across Maine. It cannot be followed on horse or awheel. Remote for detachment, narrow for chosen company, winding for leisure, lonely for contemplation, it beckons not merely north and south but upward to the body, mind and soul of man.”

- Myron Avery, In the Maine Woods, 1934

Thick undergrowth and blowdown blocks an abandoned section of the original Appalachian Trail.

For the past hour we have been making our way slowly uphill, pushing ourselves through increasingly dense growth of maple, birch, spruce, and hemlock in the woods of western Maine. We’ve been climbing over, under, and around blowdown for the past steep mile, and I have pine needles, pieces of bark, and other debris under my pack, down my back, and even in my underwear.

Every so often we stop and turn, scanning the forest for a sight change in the trees or light, perhaps an old blue blaze, searching out the next section of this old trail, which runs beside and occasionally crosses a beautiful, mossy brook between Elephant and Old Blue mountains.

Despite the effort, the inevitable obstacles of downed trees and thick brush, and the horsefly that eventually gives up on me thanks to the dense blowdown, the setting is lovely—dark, verdant, and peaceful.

Then I see it.

On a granite rock, just before a small, moss- and leaf-covered bog bridge decaying into the forest floor, I spy a white blaze—not a patch of lichen, not a wet leaf, not a relatively recent blue blaze, but a real white blaze—proof that we’re truly on the Appalachian Trail. Or rather that we are on a section of the original route of the Appalachian Trail, the longest continuously marked footpath in the world, first completed in 1937.

I’ve come to this 40-mile section—the very last piece of the original 2,000-plus miles of trail to be scouted between Maine and Georgia—for a host of reasons: history, curiosity, adventure. But mainly I’m here because of a trip log a group of college students typed up in 1934 after exploring and marking this section of trail that would complete the AT. This personal documentation of helping to build the AT has fascinated me since I first read it more than a decade ago, all the more since one of the young scouts was my great-uncle.

The Maine Problem

That blaze of white paint might never have ended up on a rock in Maine without the leadership, work ethic, and obsession of Myron Avery, admiralty lawyer, Maine native, Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC) chairman from 1931 until his death in 1952, and recruiter of trail volunteers like my uncle's college outing club.

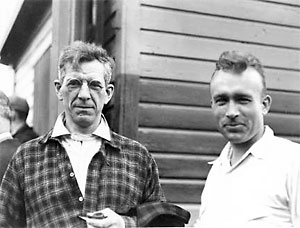

Benton MacKaye and Myron Avery. (courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)

The AT was originally conceived by Benton MacKaye in 1921 as a network of planned wilderness communities connected by a mountain trail. Intrigued hikers, or “trampers,” began construction in fits and starts in the 1920s, but the project didn’t gain steam until retired judge Arthur Perkins took it on in the late 1920s. He in turn recruited the younger Avery, who took over as Perkins’s health began to fail.

While MacKaye was concerned with the philosophical mission of the AT as a wilderness escape from the travails of modern urban life, Avery was focused on the earthly logistics of connecting sections of trail to create a continuous footpath for hiking from Maine to Georgia. He recruited volunteers, established hiking clubs, and could be found on the trail nearly every weekend, clearing brush and marking and measuring his own fair share of trail miles. In fact Avery would be the first person to walk the entire length of the AT, although not continuously. He covered much of it at least twice.

By 1933, thanks to volunteer efforts and Avery’s workaholic direction, more than a third of the trail was competed and much of the remainder was progressing well. But Maine still presented a serious challenge. “No section along the two thousand and fifty mile Appalachian Trail originally seemed more impossible of accomplishment than the estimated 250 mile section across Maine,” wrote Avery in a 1934 ATC report.

Unlike the trail systems established by the Appalachian Mountain Club in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and the Long Trail in Vermont’s Green Mountains, Maine lacked the trail infrastructure and organization to sponsor and maintain a trail. Constructing a trail through what was considered “an utter wilderness” seemed impossible to some. But Maine’s wilderness presented not only its challenges, but also its allure. “Because it leads through a virgin territory with an exceptional beauty of mountain, lake, forest and stream the Maine link should be much frequented,” wrote Avery in 1934.

A small waterfall along the original route of the Appalachian Trail.

Indeed, 70 years later the section we’re on is still exceptional. While it may not boast the highest peaks of the state, like majestic Katahdin to the north, or the dramatic features of Mahoosuc or Grafton notch to the west, it offers the best of Maine on its own scale: small ponds hidden away in dense woodlands, moderate peaks, a surprising amount of wildlife (we see moose, deer, grouse, rabbits, even a black bear). And solitude, lovely solitude. In three days we see no one else, except near two road crossings.

However some ATC leaders seriously considered moving the trail’s northern terminus from Maine’s Mount Katahdin to New Hampshire’s Mount Washington (as proposed in MacKaye’s original 1921 plan). Avery, a Katahdin devotee and the peak’s foremost expert, resisted any efforts to abandon the Maine section or its high point. He was determined to solve what some were calling “the Maine problem.”

The Missing Link

Without an organized group of local hikers and trail organizations to pull from, Avery himself spearheaded efforts to scout and blaze the trail through Maine. He called on and organized individuals and volunteer crews, often pitching in with his ever-present measuring wheel. By 1934 only one section of the entire AT between Katahdin (then considered its start) and Georgia’s Mount Oglethorpe (the southern terminus until 1959) remained to be scouted for a suitable route. This 40-mile portion in western Maine would finally link the trail from Frye Bridge (in the south near the peaks of Baldpate) to the base of 4,116-foot Saddleback Mountain in the renowned Rangeley Lakes region to the north.

For this last scouting trip, Avery turned to the Bates College Outing Club, whose members could often be found leading student groups up mountains in Maine and New Hampshire or paddling local rivers.

Led by botany professor William H. Sawyer, the group included club president Sam Fuller ’35, secretary Harold “Ace” Bailey ’36, and member Edward Aldrich ’35. For club president Sam, a 20-year-old mountain climber, fisherman, and avid outdoorsman from New Hampshire’s Conway area, the trip would be one of his proudest accomplishments. In fact, it’s his copy of the students’ trip log that brings me here.

Bates Outing Club (l-r): Professor William H. Sawyer, Samuel T. Fuller '35, unidentified (possibly a forest fire warden or logging camp boss), and Edward Aldrich '35. Photo likely taken by Harold "Ace" Baily '36 during the club's AT Scouting Trip, June 21-28, 1934.

Sam was my great-uncle and though we share a passion for the outdoors and many of the same New England peaks and trails, we never met. He was killed in action in France in 1944, earning a Silver Star for heroism and leaving behind a fiancé and family homages.

Despite his many well-deserved posthumous tributes and honors, it was “ye mountain hikers” trip log, with its descriptions of lumber camp chow, 45-pound packs, and porcupines that met bloody ends, that intrigued me more about Sam the person, Sam the outdoorsman, than a mythic dead hero.

I wondered what Sam and his companions thought of this trip and their role in building the AT. There was just enough detail in their 10-page log to make the trip real (their gear list, what they ate at each logging camp, the woes of their broken down 1926 Essex coach), but not enough to know how difficult the scouting trek really was or what it might have meant to them.

There were a few hints of course—like a section that “required an enormous amount of intestinal fortitude” and caused “a slight attack of biliousness” in one unnamed member—but I chalked some of that up to young male bravado. After all, I thought, the log mentions several tote roads and a few “well spotted” trails. Why, they didn’t even use their new tent until the last night of the weeklong journey, spending the others at logging camps, a fire warden’s cabin, a sporting camp. In fact large portions of Maine’s original route were intended to make use of sporting camps a day’s journey, approximately 10 miles, apart. Stopping at logging camps and fire wardens’ cabins for hearty meals of steak, potatoes, donuts, pie, and biscuits sounded pretty good to me.

So what about that very muddy tote road “worse than the Bad Lands in South Dakota after a week’s rain” (surely it’s dried up by now) and the “hard tough pull” straight up the precipitous C Bluff (hey, we knew where we were going, surely we could make it to the top despite “liberal spruce”).

I’d find out what Sam and his friends were made of, and perhaps a little bit about myself and the AT.

I’d follow him into the Maine woods.

Continued in “Blazing a Good Trail: The AT in Maine” (Part 2)

by Alicia MacLeay

by Alicia MacLeay