Exploring bear country offers an experience hikers and backpackers would be hard-pressed to find elsewhere. Few American landscapes rival the remote, pristine beauty of national parks like Glacier, Denali, Yosemite, and Yellowstone.

Whether you hit the trail for a day or a week, and whether you prefer campsite camaraderie or backpacking’s blissful solitude, entering the land of grizzlies and black bears comes with great responsibility.

Assure a safe trip by taking proper precautions, respecting bears’ space, and having a firm grip on how to handle yourself in a face-to-face meeting with one of nature’s most majestic and often misunderstood mammals.

Assure a safe trip by taking proper precautions, respecting bears’ space, and having a firm grip on how to handle yourself in a face-to-face meeting with one of nature’s most majestic and often misunderstood mammals.

- Where to be bear aware

- On the trail in bear country

- Camping in bear country

- Handling food in bear country

- Bear encounters

- Further resources

Where to be Bear Aware

North America is home to three types of bears: the American black bear, the brown bear, and the polar bear. Since few people enter freezing, remote polar bear country, we’ll focus on black and brown bears, where you may encounter each, and how to tell them apart.

American black bear (Ursus americanus)

Black bear in the Great Smokey Mountains (NPS Photo)

With a population estimated at around 750,000 according to the North American Bear Center, the American black bear is the most common bear species on the continent. It makes its home in 41 states, northern Mexico, and throughout Canada. Compared to their hulking Kodiak cousins, black bears are small. A male averages 275 pounds, with weight varying greatly depending on food availability.

And don’t let the name fool you — black bears come in a variety of shades. Cinnamon and tawny bears are often found in drier Western regions, and more than 80 percent of Colorado black bears are actually brown. All are known for being quite shy, prone to running away or climbing a tree if they feel threatened.

Brown bears (Ursus arctos)

While brown bears are commonly called grizzly bears, grizzlies are technically a subspecies (Ursus arctos horribilis) of browns, along with the Kodiak (Ursus arctos middendorffi). How many other brown bear subspecies there are is up for scientific debate.

Brown bear in fall (NPS Photo)

Huge, aggressive, and agile, the brown bear is the athlete of the bear family. They’re able to run up to 35 miles an hour and swim expertly. With plenty of food available they can reach 900 pounds, though the average female grizzly weighs 200 to 300 pounds, and males usually reach anywhere from 300 to 650 pounds. The colossal Kodiak, the largest subspecies of brown bear, can reach 1,500 pounds due to abundant seafood availability.

Exact numbers are impossible to determine, but an estimated 50,000 brown bears remain in North America. They live primarily in Alaska and Canada, with about 500 found along the Continental Divide in northern Montana and another 600 in Yellowstone National Park. The Kodiak bear is found only on Kodiak, Shuyak, and Afognak islands off the coast of southern Alaska.

Which bear is which?

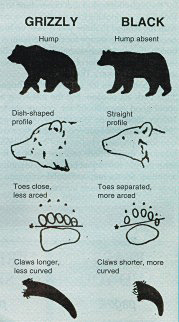

Geography and size are good clues, but they aren’t always enough to determine which bear is which, especially if you’re hiking in places where both may live. Color isn’t definite either: some black bears come in brown or blond shades, and some brown bears come in blond or black shades.

The following features will help you be certain:

Body type

Brown/grizzly bears have a pronounced, muscular shoulder hump. Black bears have a straighter back that slopes toward their rump.

Facial features

Black bears have a long, pointy nose and larger, pointed ears, while brown/grizzly heads are much larger and dish-shaped, and their small, neat ears are rounded.

Claws

Black bear claws are sharp, curved and usually no longer than two inches. Grizzly claws are rather straight, dull, and can be longer than your finger. Not that you’ll want to get close enough to examine them.

(Readers wanting to test their identification skills can check out Washington state's Bear ID program.)

On the Trail in Bear Country

Brown bears in Alaska’s Katmai National Park. (Photo: John Gookin)

Thomas Smith, a wildlife biologist with decades of experience studying human-bear interactions, says staying safe in bear country doesn’t have to be as complicated as it’s often made out to be. “In their world, they really are not looking for trouble,” he said. “Most of them will run from you, given advanced notice. As long as you give them cues you’re coming, it gives them a chance to move off.”

Generally, if you encounter a bear on the trail, you’ve either surprised it or it is one of a minute percentage of bears who, “with no provocation, see a human and see it as potentially a food item,” according to Smith.

Know the signs

A trail with a hump in the center is likely a well-traveled bear trail, since their heavy paws pack down the trail sides, leaving a raised center. Scat, about two inches in diameter, is an obvious indicator, usually quite dark and with hair or partially digested insects or plants.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists a host of other signs: Padded down vegetation with scat nearby is likely a bear’s day bed. Stripped bark, depleted berry patches, clawed or torn-apart logs, overturned rocks, and dug up roots are also telltale signs of a bear’s presence. So are dead animal parts, the smell of decay signifying a food cache, or fish remains near a stream. Even if you don’t see a bear nearby, never get close to a carcass or other food source.

Hey, Bear!

Don't fall into a trance on the trail, but look up and around and announce your presence as you hike. Chat with your group and keep children close by and within sight. Sing a song, clap your hands, call out occasionally, or talk to yourself if you’re solo — having other hikers wonder if you’re crazy is preferable to surprising a bear. Some hikers tie bells to their backpacks for a constant jingling bear alert (though how well bells work remains uncertain). When traveling upwind or near running water make more noise to be heard.

Arm yourself

With bear spray, that is. Bear spray — a substance made from capsaicin, the oily residue from hot peppers — greatly irritates a bear’s eyes and breathing passages (warning: it will do the same to you, so don’t spray it at people or straight into the wind). Always have it handy — not packed in the top of your pack, not one zipper away, but in a hip holster (it should come with one when you purchase it) or a side pack pocket.

Bear spray should be used as a last line of defense against a charging bear. Never spray it on people, on your gear (spraying it on your tent might even attract a bear), or at a non-charging bear.

Learn how to properly use bear spray and know the spraying guidelines and range before you head out. Practice removing your spray from its holster in anticipation of various, surprise encounters. Be prepared to aim at the bear’s face or in a cloud the bear has to pass through to get to you. The Center for Wildlife Information recommends a minimum spray distance of 25 feet and spraying for at least six seconds to give the bear time to stop or divert its charge.

All bear sprays sold in the United States must be registered with the Environmental Protection Agency. Health Canada registers products for use in Canada.

If flying, check current airline and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations before packing bear spray. Currently, the FAA has restrictions against traveling with certain non-medicinal aerosols. You’ll likely need to purchase bear spray once you arrive at your destination.

Far better than bullets

Never rely on shooting your way out of a bear encounter. Recent research shows that using your brain and your bear spray is a far safer option. In 2008, Smith and three colleagues published the study“Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska” in the Journal of Wildlife Management, assessing the use of bear spray in Alaska from 1985 to 2006. In 72 bear encounters involving 150 people who used bear spray, a bear touched a person three times, resulting in very minor injuries. According to the study’s Abstract, “Of all persons carrying sprays, 98% were uninjured by bears in close-range encounters.”

In a separate research project by Smith (using data from the Alaska Bear Attacks Database Project he’s worked on), of 150 people who used firearms, bears killed 17 people, seriously mauled 35, and injured many others.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s Bear Spray vs. Bullets fact sheet, “No deterrent is 100% effective, but compared to all others, including firearms, proper use of bear spray has proven to be the best method for fending off threatening and attacking bears, and for preventing injury to the person and animal involved.”

Consider the animal, too — bear spray results in temporary discomfort. Bullets wound and kill. And many parks, including Denali and Yosemite, prohibit firearms or, at the very least, don’t allow you to carry them loaded on the trail.

Camping in Bear Country

When camping in bear country, avoid bringing anything with a scent. Just because it’s not edible doesn’t mean it won’t draw a bear to your camp, so ditch perfumes and use unscented deodorant and soap. When choosing a backcountry campsite, keep in mind that lakeshores or alpine meadows are lovely places to camp, but bears prefer them too.

Inspect your site to make sure it’s clean, trash-free, and that it will allow enough space between your camp kitchen, sleeping area, and where you’ll store or hang your food.

John Gookin and Tom Reed, authors of NOLS Bear Essentials: Hiking and Camping in Bear Country, recommend about 320 feet between each area, in a triangle set-up. If outdoor toilets aren’t available, go far and away to do your business, and bury it deep. Keep your camp spotless, collecting all trash in a sealable bag.

Handling Food in Bear Country

A fed bear is a dead bear. We’ve all heard the mantra. Human food is incredibly enticing to bears. Bear noses are 100 times more sensitive than ours, and they have excellent memories, often returning to places they’ve found “positive food rewards” like a sandwich or Twinkies. Yosemite, for instance, is ridden with smart, food-conditioned bears that have become expert thieves. A bear that raids campsites usually ends up being destroyed — a terrible and unnecessary result of careless human behavior. Dave Smith, author of Backcountry Bear Basics: The Definitive Guide to Avoiding Unpleasant Encounters, sums it up simply: “Once bears get food from humans, they’re addicts, and most addicts die young.”

Never stash food anywhere other than an approved storage container. Your options are a metal bear box, a plastic bear resistant food canister, or a stuff sack hung properly from a tree or bear pole, depending on the rules wherever you’re headed. Research the rules and practices for the area you’ll be visiting before you get there.

What goes in

Whatever method you use, Backcountry Bear Basics recommends the following be safely stashed:

- Food and beverages

- Stoves and fuel

- Cooking utensils

- Clothes in which you’ve cooked

- Toiletries

- Pet food

- Trash

Bear boxes

Many areas, like Yosemite and Denali National Parks, provide bear boxes in campgrounds and require you to use them. When these metal food lockers are closed and locked correctly, a bear can still smell the food but can’t access it. Never leave a bear box unlatched or open, even if you’re only stepping away for a moment. If a bear box is not available in your campground, secure your stash in your vehicle’s trunk.

Bear canisters

These durable, plastic containers that close and lock tightly are used when backpacking, where bear boxes aren’t available or when there aren’t substantial tree limbs from which to hang food. Yosemite and Denali require them for the backcountry, and some parks even require you to have an approved brand of canister — check websites in advance so you make the proper purchase or rental, and practice packing it before your trip. Information on approved containers can be found at the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee or the Sierra Interagency Black Bear Group’s websites.

The National Park Service recommends placing bear canisters on the ground 100 feet or more away from your campsite, never near a cliff, big hill, or water source. One helpful hint: place cookware on top of your canister to create an instant bear alarm. Bulkiness is an issue, but you can repackage your food and toiletries, and choose dense foods that are high in calories. It’s better to heft the canister on the trail than to wake up one morning, three days from civilization, to find only empty food wrappers and bear spit.

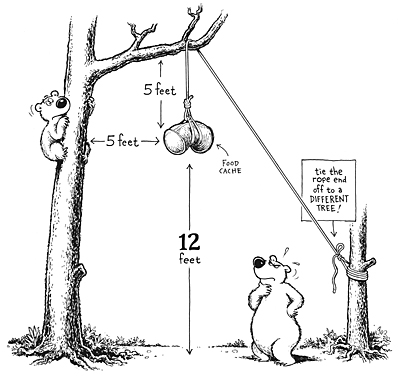

Food hanging

If you’re not required by park law to have a bear canister or use a box, you must hang your food in a stuff sack. Some parks, like Yellowstone, provide backcountry food hanging poles, but a suitable tree works too. In NOLS Bear Essentials, Gookin and Reed recommend your stash be 12 feet above ground and five feet from large tree limbs. A variety of rope hang techniques are featured in their book, ranging from the Single-Rope Hang to a “High Line Hang and Tree Climb” technique that you won’t want to attempt without some prior practice or the help of a professional engineer.

A diagram from NOLS Bear Essentials illustrates the single-rope hang, one of several methods for hanging your food. (Illustration by Mike Clelland)

Here’s how to pull off a single-rope hang:

- Grab your food bag, the sturdy 50-foot rope you’ve surely remembered to pack, and find a proper tree limb, about 20 feet above the ground with no branches below it.

- Weight one rope end with a rock or carabiner and toss over the limb (repeat until you actually pull it off).

- Tie the food bags on in a secure knot, and hoist them about 12 feet above.

- Tie off the rope on a different tree nearby.

Is it foolproof? No. Could a visiting, determined bear chew through your rope and enjoy a tasty snack while you sleep? Sure.

For this reason, some backpackers take a combo approach, storing some food in a hanging stuff sack and the rest in a canister.

Others opt for using one of the more complicated hanging techniques in Gookin and Reed’s book, which include numerous trees and ropes and some shimmying. Practice before your backcountry excursion and have your method(s) down pat.

Cooking and cleanliness

Avoid greasy foods that splatter (leave the bacon at home) and try to avoid leftovers. If you’ve hunted or fished, do not clean fish or game in camp. Wash all dishes and utensils with a non-scented soap. Any leftover food must be included in your trash, and as on any camping or backpacking trip, always adhere to proper Leave No Trace principles. If you pack it in, you pack it out, and that means every single food wrapper, tissue, bit of trash, and band-aid. Leave the woods as you found it.

Disposing of grey/wastewater can require extra care. Leave No Trace recommends the following in its Rocky Mountain Skills & Ethics Booklet:

Disposing of wastewater in bear country is tricky. Once again, your main goal is to keep odors out of camp. If you are camped by a large volume river—at least 10 feet wide with substantial depth—you can pour strained wash water directly into the river to help disperse any odor.

If you are not by a river, consider digging a small hole (6-8" deep cathole) and sumping your wastewater. This practice concentrates odors in one safe location well away from your camp, however, animals may be attracted to the smell and dig up the hole in search of food. For this reason, sumping is not recommended in areas of high use. In these places, you should walk well away from camp and scatter your wastewater.

Always research and follow local agency regulations and suggestions for your area.

Bear Encounters

You’ve been careful and followed all the rules but now find yourself in the path of a grizzly or see two cute black bear cubs foraging with mom. Hundreds of books and websites offer countless tactics — waving your hands about, throwing rocks, lying down if a bear charges.

A brown bear at Hallo Bay in Katmai National Park shows off its “cowboy walk” to look tough (or, in John Gookin’s words, “be a real bad-ass”). (Photo: John Gookin)

Nonsense, according to Tom Smith. “Carry a deterrent, make noise and act appropriately, and let the bear figure you out. Stand your ground. If it charges, you spray it. There’s no room for this other stuff,” he said. So here are the steps, as simple as possible, to handling a bear encounter:

- Be calm. Don’t run; you’ll flip the bear’s “chase” switch.

- If you come upon a bear that doesn’t notice you, leave quietly and immediately. This isn’t your “Grizzly Man” moment; don’t fumble around for a camera, approach it, or talk to it.

- If the bear does notice you or you surprise it, speak in a normal tone of voice while slowly reaching for your bear spray. Back up, but don’t turn away from the bear. “Give it a chance to recognize you’re not a threat and to leave the area,” Smith advises. If it leaves, you leave in the opposite direction.

- If the bear stands up, it’s trying to get a better whiff of you. However, if it’s snorting, huffing, or making clicking noises with its jaws, it is getting angry. Continue speaking and backing up, and don’t lose that grip on your 12-ounce can of protection.

- If the bear approaches, it might be bluffing to tell you it’s tough. Don’t wait to find out. Fire your bear spray as soon as the bear is in recommended spraying range. The National Park Service advises aiming for the face but slightly downward because the spray billows upward. Fire a second shot if the first one doesn’t stop the bear’s charge, emptying the can if you have to. The bear should quickly find itself in severe discomfort, and you should find yourself booking down the trail as fast as your shaky legs can carry you.

-

In the very rare instance that the bear spray fails, stand your ground. If it’s a black bear attacking you, always fight back — yell, scream, punch, kick. According to the Colorado Division of Wildlife, people have successfully defended themselves from black bear attacks with knives, trekking poles, and their bare hands.

Brown bears at Hallo Bay in Katmai National Park head off after a flare is set off. (Photo: John Gookin) - No matter what species of bear you’ve encountered, never hit the ground and play dead unless the bear has knocked you down. “Telling them you’re submissive and passive and they’re dominant? I would not give them that message,” Smith said.

- If you’ve encountered a grizzly and it approaches, is unaffected by bear spray (highly unlikely), and knocks you down, then playing dead is a good plan. According to Backcountry Bear Basics, “a startled grizzly — a grizzly acting defensively — generally does not cause serious injuries if you play dead.” However, if you’ve been playing dead for a few minutes and the bear hasn’t left, doesn’t seem as angry, and may be settling in to make you a meal, then you must switch gears and fight. “There are people who fought back with grizzly bears and that worked for them,” Smith said. “But we’re talking about the few who lived to tell about it.”

When exploring bear country, your first and best tool of defense is your brain. Never make assumptions about bear behavior or take a nonchalant, “it won’t happen to me” approach. Research the area and contact local wildlife or park officials for their specific rules and recommendations. Carry bear spray, but know that it’s not a substitute for taking all the proper precautions.

Keep your cool, make smart choices, and maintain respect for the bears’ natural habitat, perhaps keeping in mind the words of naturalist and author Henry Beston: “The animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not our brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations caught with ourselves in the net of life and time.”

The Author’s Source List, and other bear resources:

Books

Backcountry Bear Basics: The Definitive Guide to Avoiding Unpleasant Encounters

Dave Smith

NOLS Bear Essentials: Hiking and Camping in Bear Country

John Gookin and Tom Reed

Hiking in Bear Country

Keith Scott

BEARS: Behavior, Ecology, Conservation

Erwin A. Bauer

In the Company of Wild Bears: A Celebration of Backcountry Grizzlies and Black Bears

Howard Smith

Bears: Wild Guide

Charles Fergus

Expert Interviews

Tom Smith: associate professor of wildlife science and research wildlife biologist, Brigham Young University; U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center - Biological Science Office

John Gookin: curriculum and research manager and instructor, NOLS; author of NOLS Bear Essentials: Hiking and Camping in Bear Country

Tom Reed: former NOLS instructor; currently Montana/Wyoming backcountry organizer for Trout Unlimited; author of NOLS Bear Essentials: Hiking and Camping in Bear Country

Websites

Colorado Division of Wildlife

Camping & Hiking in Bear Country

The North American Bear Center

www.bear.org

National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park

Minimizing the Dangers of a Bear Encounter

Backcountry Camping & Hiking

Bear Pepper Spray Video Transcript

National Park Service, Denali National Park & Preserve

Backcountry Information

U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center

Bear Pepper Spray: Research and Information by Tom Smith

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Mountain-Prairie Region

Environmental Protection Agency

Bear Deterrents

Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee

www.igbconline.org

The American Bear Association

Camping and Hiking in Black Bear Country

Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center

Camping and Hiking in Bear Country

Center for Wildlife Information

www.centerforwildlifeinformation.org

Leave No Trace

www.lnt.org

by Bobbi Maiers

by Bobbi Maiers

What does Tom Reed, co-author of

What does Tom Reed, co-author of