View of Washington’s Mount Rainier from the PCT, Snowgrass Flat, Goat Rocks Wilderness. (Photo by Kristen Isakson, courtesy of PCTA)

Are you considering or planning a thru-hike for next year (or even just for “some day”)? Sorting through a deluge of advice and wondering which to pay attention to? Successful backpackers can tell you what really matters.

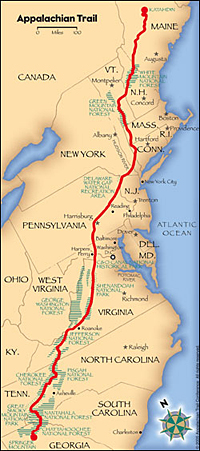

Thousands of people set out every spring to hike one of America’s long trails, such as the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, or the Continental Divide Trail. Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, they anticipate spending the next five or six months traipsing through woods and over mountains, earning bragging rights that will last them all their lives.

Come autumn, only a relative handful of these eager souls will finish the trail. The rest will drop out along the way.

What makes the difference?

Answers to that question from hardcore backpackers and successful thru-hikers vary widely. What works best in terms of physical training or gear choices is very individual. Even then success isn’t assured for anyone: even the best-prepared backpacker’s plans can be thwarted by a stress fracture or an early-season snowstorm. But Triple Crown hikers — those who have completed all three of those long trails — generally agree on certain characteristics essential to success, especially preparation, perseverance, and flexibility.

Those are also the keys to enjoying shorter trails, such as the 211-mile John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada, the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail in California and Nevada, and the 273-mile Long Trail in Vermont, the oldest long-distance footpath in the United States. All are terrific ways to prepare for a longer trek.

By now, people planning to hike the Appalachian Trail (AT), Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), or Continental Divide Trail (CDT) next year should be deep in the preparation stage. The first choice, of course, is: which trail?

- The Appalachian Trail, running 2,178 miles from Georgia to Maine, is by far the best known and the most popular. With its white blazes marking the trail, shelters every several miles, and easy access to roads and towns, the AT annually attracts well over a thousand wannabe thru-hikers … who quickly discover just how challenging it really is. Typically, around one in four make it the whole way.

- Only about 300 thru-hikers tackle the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail each year, partly because it appears much more daunting. PCT thru-hikers begin their walk in the hot, dry desert at the California-Mexico border and climb through a succession of High Sierra passes, many exceeding 10,000 feet, before pushing through the Northwest’s stormy weather on their way to Canada. Roughly 60 percent finish.

- Few except the very experienced tackle the Continental Divide Trail, which isn’t even a true trail yet — just a route from Canada to Mexico along the spine of the Rockies, roughly 3,100 miles long. Only a few dozen people attempt it each year and map and compass skills are crucial.

- While the AT, PCT, and CDT are probably the best known long trails in the United States, other national scenic trails (some still in progress) include the 4,600-mile North Country Trail, the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail, the 1,000-mile Ice Age Trail, and the 1,100-mile Florida Trail. Canada’s long trails include the 885-km (550-mile) Bruce Trail, the 1,045-km (649-mile) International Appalachian Trail, and (in the works) a coast-to-cast National Hiking Trail.

Having chosen his or her trail, the wise backpacker investigates all available resources, including websites, books, magazines, and trail journals (see resources below). He or she may attend programs to learn or review specific skills (map and compass reading or first aid, say), or interview successful backpackers in person or online. Then he begins buying gear and getting into shape. These two chores are best begun many months before a thru-hike starts.

Gear

Wise thru-hikers preparing for cold, wet weather choose the lightest-weight gear they can afford before heading into the mountains. Here, snow clings to the North Cascades even in July. (Photo by Gary Chambers; click for PCT videos)

Triple-Crown hiker Jackie McDonnell, better known by her trail name Yogi, says the best way to keep pack weight at a minimum is to keep gear at a minimum and get the lightest version of each item that you can afford. (Unfortunately, the lowest weight tends to correspond with the highest price, for everything from cook pots and tent stakes to ice axes and sleeping bags.)

On the other hand, since Yogi frequently changes her gear, even on the trail, her most important item may be the “800” number for REI stores. “I could order anything and get it at the next town,” she said.

Triple Crowner David Rainey, aka Pineneedle, has a simple formula to explain why he carries only the essentials and how he manages to move so quickly: “The less you carry, the faster you go. And the faster you go, the less you need to carry.”

Of course, the bare essentials differ from one person to another. Karen Somers, known on the trail as Nocona, wouldn’t step foot in the Sierra without her RailRiders Eco-Mesh shirt (proof against biting insects and sunburn) and a mosquito head net. John Muir Trail veteran Alice Bodnar found a comprehensive foot care kit was the most valuable item in her pack. My favorite possession is my MSR PocketRocket stove. Ask other thru-hikers, especially those with similar hiking styles to yours, what worked for them.

The author (right), husband Gary Chambers, and their Eureka! Zeus 3EXO tent in the Southern California desert during their family’s 2004 PCT thru-hike. (Photo by Mary Chambers; click for PCT videos)

On the other hand, plenty of backpackers give little thought to mosquitoes, blisters, or cooking on the trail, and do just fine. But the successful ones agree that a shelter of some sort is crucial, preferably a lightweight tent.

A sheet of nylon might be enough for the ultra-light crowd, but for most people, a tent is best. It keeps out rain, snakes, mice, and mosquitoes, and it gives shelter from the wind and the cold. It gives you a place to stow your belongings and organize your stuff when you camp with other hikers. And a tent provides one more thing that’s often in short supply on the trail, especially the more popular ones: privacy.

Whatever gear you choose, familiarize yourself with it and break in any footwear before your thru-hike begins.

Training

As with gear, advice for getting into shape is all over the map:

-

Yogi likes to start the trail completely conditioned, which isn’t easy while working 50 hours a week during the off-season, in her home state of Kansas. She starts walking an hour a day, six days a week, about nine months before she wants to start a trip. During the last three months, she adds ankle weights, and swaps 20 minutes of walking for 20 minutes on a stepper.

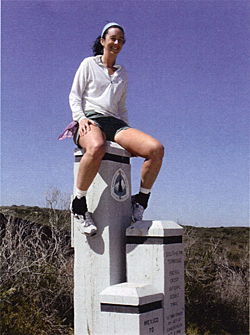

Jackie McDonnell, aka Yogi, perches atop the monument at the south end of the Pacific Crest Trail on the Mexico-California border. Yogi has written handbooks for the PCT and the CDT. (Photo courtesy Jackie McDonnell)

- Nocona recommends traveling to a point near the trailhead a week ahead of your start date to adjust to the heat during day hikes, especially out West.

- Alice found high-mileage backpacking trips on weekends just before a big hike the key to a good trip.

- Trail angel Donna Saufley, who took up backpacking after meeting and helping hundreds of thru-hikers, tries to match her training regimen to the elevation gains and losses she’ll experience on the trail. “Flights of stairs would work for those locations without mountains,” she suggested.

What it comes down to is building up your strengths and skills, discovering your weaknesses, and then acting on what you’ve learned. Try to fit in at least one backpacking trip of 10 to 14 days that includes terrain similar to the harder parts of your chosen trail a few months or even a year ahead of time, and take several shorter trips as close to your anticipated hike as possible.

If you plan to travel alone, then practice alone. There’s a huge difference between going alone and being with another person. Until you actually do it, you don’t know if you can hike to your backcountry campsite all by your lonesome, set up your tent, and then actually get a good night’s rest despite all the strange noises emanating from the dark forest.

And if you do have a prospective hiking partner, be sure to practice with him or her. There’s a popular misconception that you can advertise for a hiking partner online, meet up with this person for the first time at the trailhead, and by some miracle you’ll both have the same goals, hiking style, daily mileage capacity, ability to deal with the weather, need for rest days, and so on.

Yogi is adamant: “Never agree to hike with a partner.” Unless the partner is a spouse or significant other — and someone you’ve done a lot of backpacking with already — don’t do it. Instead, start on your own and you’ll soon discover fellow backpackers who will make good companions for a section or even the entire trail.

Up next, Part 2: What am I doing out here on the trail? And what am I going to eat?

Resources for planning an AT, PCT, or CD thru-hike include:

(Check online and with other thru-hikers for additional publications and resources, as new material is published every year.)

|

Appalachian Trail Conservancy www.appalachiantrail.org The ATC provides a wealth of information on planning an AT thru-hike on its website. The ATC publishes official trail guides and maps, the Appalachian Trail Data Book, and the AT Thru-Hikers’ Companion, both updated annually. Members receive the magazine A.T. Journeys and discounts on maps and books purchased from the extensive online Appalachian Trail Store. |

| Pacific Crest Trail Association www.pcta.org PCTA members receive the PCT Communicator magazine. The website has answers to FAQ, information on planning a thru-hike, and maps, guides, and planning books for sale. The PCTA issues, upon request, Thru-Permits for trips of 500 miles or more on the trail, plus special permits for side trips to Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the Lower 48 States. |

|

|

Continental Divide Trail Alliance |

| Continental Divide Trail Society www.cdtsociety.org The CDTS publishes the Guide to the Continental Divide Trail, a series of guidebooks and supplements that provide a mile-by-mile description of the Continental Divide Trail. |

|

|

Wilderness Press, Berkeley www.wildernesspress.com Wilderness Press, publisher of outdoor hiking books and maps for 40 years, publishes the three “official” PCT guidebooks — for Southern California, Northern California, and Oregon/Washington — and the PCT Data Book. Other titles cover hiking maps, planning, trails, skills, and narratives. (Wilderness Press also published Zero Days, the author’s book on her family’s 2004 PCT thru-hike.) |

|

Pocket PCT PCT thru-hiker Paul Bodnar just published Pocket PCT: An Elevation Guide to the Pacific Crest Trail available at www.lulu.com/content/paperback-book/pocket-pct/7555165. It provides an elevation profile of the entire PCT, mile-by-mile markings for water sources (graded by reliability), resupply points, and other landmarks (such as other trails, roads, etc.). |

|

Yogi’s Guides www.pcthandbook.com Triple Crowner Jackie McDonnell publishes Yogi’s PCT Handbook, the companion book for the PCT, and updates it frequently. (The old Town Guide is out of date and out of print; the PCTA recommends using Yogi’s handbook instead.) Yogi also has published a CDT companion, Yogi’s CDT Handbook. |

Read the full series:

“Planning a Thru-Hike: Part 1”: tips on choosing a trail, gear, training, and resources.

“Planning a Thru-Hike Part 2”: What am I doing out here? And what am I going to eat and drink?

“Planning a Thru-Hike: Part 3”: advice from Triple Crown thru-hikers.

“Planning a Thru-Hike Part 4”: advice from trail angels.

by Barbara Egbert

by Barbara Egbert